A Natural history of music

Equal tempered scale

Fixed frequencies

"Sacred" frequencies 432 Hz…

An advice to musicians

Renaissance of Vedic music

A SHORT "NATURAL" HISTORY OF MUSIC

Music is so natural...

When we're happy, we naturally feel like singing or whistling, like birds in springtime.

Sometimes a melody comes to us, sometimes quite simple, even simplistic, just two or three notes repeated over and over again, but they make us happy.

What is the magic behind it?

Nothing magical, just the wonderful world of HARMONICS.

Music IS Harmonics!

WHAT ARE HARMONICS?

The pitch of a sound is expressed by its frequency, measured in Hertz or pulsations per second.

However, the sound produced by an instrument or the voice is never a single frequency. It is made up of a dominant frequency and its many harmonics, which are multiples of the dominant frequency.

The word "harmonics" indicates that these components generate harmony.

Harmony is the orderly and pleasing association of elements in a whole.

The words "orderly" and "pleasing" indicate both mathematically precise and aesthetically pleasing.

Harmony is the hallmark of a natural expression, of the laws of nature.

A note is therefore a set of harmonious sounds.

Without going into too much detail... when a voice or the sound of an instrument is rich in harmonics, the charm of these harmonics inspires us to sing our own notes that are also in harmony with those harmonics.

And music is born...

Because each note has a particular color or mood or emotion we feel in the notes a closeness to our own emotions.

So the impulse to sing as an expression of our joy is natural.

Just as in a language, there are bonds between the syllables of a word and bounds between the words, in music there's harmony within the notes (the harmonics) and harmony between the notes.

- A note by itself, because it's made up of harmonics, is always "harmonious".

- When there's harmony between several notes, it's because they have harmonics in common. We can call them "harmonic notes".

- A homogeneous set of "harmonic notes" is a "harmonic scale".

How many harmonic scales are there?

Thousands!

Because harmonic scales are natural, they have been used in traditional music throughout the world.

Of all the world's musical genres, Indian classical music has preserved the greatest number of harmonic scales (several hundred).

Music is natural. We are all musicians.

Since the dawn of time, in all simplicity and innocence, music has been a natural way of expressing our emotions and enjoy them.

~ Maharishi Mahesh Yogi

Originally, music was improvised. Musicians let themselves be guided by their inspiration of the moment. But as says the beautiful Brazilian song Canções e Mementos: "there are moments that marry song”. And those magical moments come when they please...

So, by memorizing their compositions, musicians could more easily recall the subtleties of the notes and scales that came to them out of inspiration.

Then, to convey them better, the compositions had to be written down.

As composers continued to draw inspiration from their elders, the beauty and complexity of compositions sometimes developed to the point of eclipsing the simple natural beauty of the notes themselves.

Little by little, music moved from the street (troubadours) to chamber music, salon music, concert music... music for the elite. From an innocent, improvised music from the heart, music slowly evolved to a music of the learned composers and performers.

Over the centuries, as compositions took precedence over improvisation, music became more and more elaborate, but lost the spontaneity, sensitivity and beauty inherent in the notes themselves when they are pure.

Then, in the industrial age, music "benefited" from several technological advances that were not always in the direction of refinement:

Solid metal wires replaced gut strings for a purer, louder sound (fortepiano, guitar...). But the simplicity of tuning (from the harpsichord to the piano) and the freedom to move notes by feel (metal frets fixed in wood for the guitar...) got lost.

The two most catastrophic "evolutions" for the purity and refinement of music were the equal tempered scale and the fixing of note frequencies.

Those two sentences Mozart said illustrate the extent of the damage caused by the equal tempered scale:

- "My job is to put together the notes that love each other".

Notes that "love each other" are notes that have an affinity, a common trait that unites them. "Birds of the same feather flock together". And to play with this affinity is the musician's work: on the one hand, by "marrying" the notes of the scale he has chosen, and on the other, by selecting from the infinite variety of notes the few he could "marry" into a beautiful family (scale) where all the notes love each other.

- "I'll kill anyone who plays my music with that"Mozart said when he heard the tempered scale. With "that", yuck!

In Mozart's time and before, the instrument (harpsichord) had to be tuned before each performance. For such and such a musical piece, the fifth had to be slightly lowered, the fourth slightly raised...

THE EQUAL TEMPERED SCALE

For reasons of convenience (to avoid retuning the piano and be able to switch quickly from one mode to another), the idea came to create an "equal temperament".

Equal tempered scale meant wiping the slate clean of all the subtleties of the different temperaments (scales) by placing the 12 steps (semitones of the chromatic scale) at regular intervals.

- Can you imagine the revolution this "equal tempered scale" represented at the time?

Music went from analog to digital, literally!

Since the adoption of the equal tempered scale, what we still call "music" is no more than an imitation of music, because the intimate and delicate relationship (the harmonics) that united the notes has disappeared.

Today, almost everyone plays Mozart (and all the great composers) with that!

It's the harmony that binds the notes together that makes "music soothe the soul".

In the equal tempered scale, apart from the octave, there is no harmony, no resonance between the notes.

This loss of refinement has certainly influenced people's psychology and happiness, because the "notes that love each other" Mozart spoke of are made of these refined harmonics.

And if the adoption of the non-harmonic equal tempered scale coincided with the end of great composers, the end of genius, of musical inspiration, is this a coincidence?

The experience of refinement is the key to happiness.

Why can't we hear the equal tempered scale is distorted and out of tune?

- We've heard the equal tempered scale from a very early age, we've heard only this, and we've learned that "this" is music.

- The virtuosity of the musicians, the elaborate, catchy, charming melodies and rhythms, and the poetry of the lyrics, conceal from us the uniform, unnatural nature of this scale.

- And last but not the least: our brain creates ITS own reality!

It has the capacity, on its own, to correct an error, especially when it makes the perception more aesthetic or conforms to a belief or habit...

A good example, the perfect chord: C E G.

It's called "perfect" because these three notes (when harmonic) have a very intimate relationship with each other. The ratio between G and C (a pure fifth) is 3/2. This means that while G makes 3 waves, C makes 2. So, every 6 waves, their peaks come together, i.e. for a G at 300 Hz, the waves of C and G are in phase 50 times per second.

Relationship between the three notes of the perfect chord

| Notes | C | E | G |

|---|---|---|---|

| Harmonic scale | |||

| Ratio | 1 | 5/4 | 3/2 |

| Decimal | 1 | 1,25 | 1,5 |

| Equal tempered scale | |||

| Decimal | 1 | 1,259992… | 1.498307… |

You may note:

- The simple numbers of the harmonic notes and the complex numbers of the same notes in the equal tempered scale

- The tiny difference between the two scales.

Because the difference is so small, our brain is able to correct the error and give us the illusion that they are in harmony.

Consequences

When we listen to music in equal tempered scale, our brain has to compensate constantly to make us "hear" that the music is in tune. This compensation is extra work that prevents the listener from being truly relaxed, and prevents him from appreciating the finer nuances of the music and being carried along by it to more peaceful states of greater happiness and inner silence.

Through continuous practice, the brains of seasoned musicians develop this capacity for correction into second nature. As a result, they hear in tune the out-of-tune notes of the equal tempered, and because they no longer make compensatory efforts, they enjoy the music more.

This is why Western classical music is so much more appreciated by music fans than by people with untrained "ears".

In contrast, children and primitive peoples who listen to music in harmonic scales love it right from the start.

FIXING THE FREQUENCIES OF NOTES

At the same time, the importance of setting note frequencies also became apparent.

- What were the advantages of establishing a conventional reference note (A)?

- To ensure that the various instruments in the orchestra played the same notes, otherwise there would be cacophony.

- To adapt to the register (the possible pitch of the notes) of the instruments and the singers' voices.

Historically, the lead instrument would start playing the tonic, and the other instruments would tune to this note.

Once agreed on the tonic, the reference note, musicians find out by ear where the other notes of the scale are placed.

The transition to the equal tempered scale must have been very upsetting for sensitive musicians, because they could no longer go by their intuition. They had to learn to play out of tune and keep on playing out of tune..

It was at this point that the importance of fixing note frequencies became apparent. Since all the notes in this new scale are at regular intervals, fixing a reference note became very important, since all the other notes were fixed at the same time.

Strangely enough... it was a little before this time that were invented:

- The technology for accurately counting seconds,

- The technology for counting the frequencies of a vibrating string per second.

Together, these two technological advances made it possible to calculate frequencies. Before that, knowing a frequency was of absolutely no importance. For this reason, tuning forks didn't count Hertz (cycles per second) simply because it was impossible to count string vibration frequencies...

Moreover, since Pythagoras, and long before him since he studied music in India, the numbers used to qualify notes were known as harmonic RATIOS.

Ratios indeed characterize the relationships between notes. These numbers can be described as "relative" because they always relate one number to another, and not to its absolute value. A number by itself had no value in music.

Examples of interval ratios between notes: 3/2 a typical fifth (interval between C and G), 4/3 a typical fourth (interval between C and F), 5/4 a typical fourth (interval between C and E), 9/8 for a second (from C to D)...

By "typical" interval we mean that there are others, but this one is the most obvious.

With the introduction of the equal tempered scale and fixed frequencies, we moved on to

These two "inventions" made it easier to tune many instruments and change modes during a concert... But in terms of musical refinement, it was a disaster, not a step forward at all.

~ Ross W. Duffin - How Equal Temperament Ruined Harmony (and Why You Should Care)

“SACRED” FREQUENCIES – 432 Hz…

With the destruction of harmony by the equal tempered scale, we thought we'd hit rock bottom of music. But no.

Now we're promised the wonders of tuning our instruments to a specific frequency.

Read the article on 432 Hz

AN ADVICE TO MUSICIANS

Music is not a language of sounds.

It is a language of relationships, of links, of union, between sounds.

Music is a language of love.

Instead of wasting your time with this 432 Hz stupidity, start by putting aside your synths, pianos and other instruments tuned to this damned equal tempered scale. Sing, and allow the loving notes to come to you. Listen to them, feel them, let their beauty touch you. An almost infinite number of notes and harmonic scales are naturally present at the finest levels of nature, at the finest levels of our own emotions. It's up to you to find them. They are the secret of musical refinement.

Not an easy task...

RENAISSANCE OF VEDIC MUSIC

This little natural history of music has its gaps.

While it's true that music is essentially natural - little children can sing before they can speak - the "evolutionary" point of view we present doesn't explain how music evolved from a stammering stage to the highly elaborate architecture of scales used by all the great civilizations of the world.

Let's think for a moment about the incredible diversity and richness that this nearly universal principle gives to music: the octave, a whole musical world, is divided into 12 segments, of which we choose to keep only 7 (sometimes 5, 6 or 8...) whose multiple combinations allow us to create a multitude of beautiful scales, each with its own energy, mood and emotions.

What magic!

How and by whom were these universal laws of music discovered?

In botany, we know that the region with the greatest number of varieties of a species is likely to be the region of origin of that species.

The greatest number and diversity of harmonic scales based on the 12-octave division can be found in Indian classical music, with over 300 listed and 150 still alive.

Chinese, Japanese, Arabic and Greek scales (the origins of Western music) are all present in Indian classical music.

Yehudi Menuhin, the greatest violinist of the 20th century, marveled at the richness and “incredible purity and refinement” of Indian classical music.

To do it justice, Indian classical music should be renamed “Vedic Music” or “Gandharva Veda”.

Way beyond Indian culture, Veda is the total knowledge of the laws of nature.

Just as mathematics, medicine, art, astrology and many other sciences come from Veda, so music comes from Veda.

Veda is not a human creation. It was perceived by the ancient sages as the impulses of consciousness, of their own consciousness.

Uncreated and eternal, Veda is the “constitution of the universe”.

Because Vedic knowledge is complete, it is indestructible.

You can get an idea of the perfect structure and coherence of the Vedic sciences by reading the article (in PDF) Relationship between the notes of Indian music, the planets and signs of the zodiac in Jyotish (Vedic astrology)

When knowledge ceases to be complete, it becomes fragile, does not resist the passage of time, becomes diluted and gets lost. This is the fate that has befallen music and all the sciences whose origin is the Veda.

Time is not linear, it's cyclical. From age to age, knowledge is lost and reborn...

The evolution of music over the last few centuries has focused on its complexity, at the cost of its original purity and effectiveness in creating happiness and harmony, which have diminished.

The purpose of Vedic music, far more than entertainment, is to stimulate, reinforce and balance the laws of nature that are active at different times of the day and night.

By helping to create and maintain harmony in the environment, the powerful technology of Vedic music enables man to assume his role in the smooth running of the universe.

Dhrupad music

Dhrupad music is the purest form of Vedic music. It has preserved the knowledge of the different harmonic scales (ragas), whose very precise position of each note is the secret of their refinement.

This pure marvel of harmony, almost unknown in the West, and kept very confidential in India, its country of origin, after having almost disappeared, is now taking off again all over the world.

Where can you study Dhrupad music?

In India:

♦ With the Gundecha brothers: dhrupad.org

Ramakant Gundecha has devoted himself to passing on the note-accuracy he learned from Ustad Zia Mohiuddin Dagar (1929 - 1990), the greatest specialist in the note-accuracy of the ragas.

♦ With Uday Bhawalkar: dhrupadgurukul.com

Uday Bhawalkar studied Dhrupad with the same teachers as the Gundecha brothers, from the prestigious Dagar lineage that counts 19 generations of Dhrupad experts.

In France:

♦ With Shivala : dhrupadmusic.com

Shivala has been studying Dhrupad with the Gundecha brothers in India since 2001.

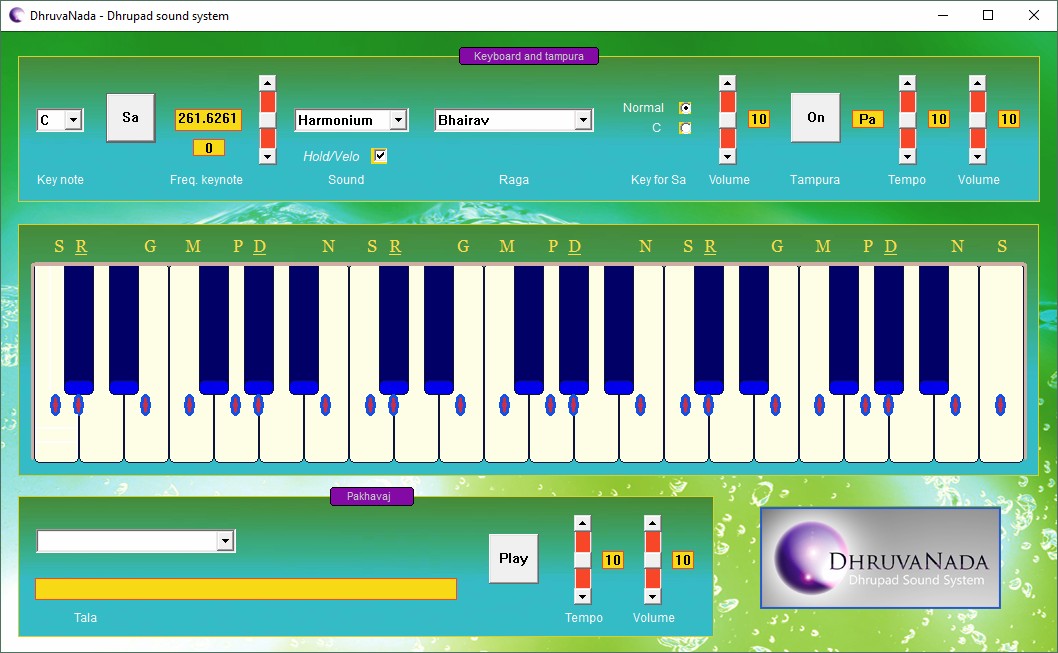

DhruvaNada - The Dhrupad software

The precious Ragas of Dhrupad are now available on your computer.

Thanks to more than 10 years' hard work by Ramakant Gundecha, Shivala, and Ketil Helmersberg, the DhruvaNada software was born (still in Beta version). It allows you to play and hear the correct scales of the Ragas.

DhruvaNada software has three goals:

- To save the precious and disappearing Dhrupad scales

- To help students of Indian music find the right tuning of the notes for the Ragas.

- To develop the musical creativity of all musicians beyond their imagination, by opening up the refined world of these scales hitherto reserved for India's rare Dhrupad singers.

It is certainly not a coincidence that this rediscovery of music's subtlest refinement and most powerful harmonizing power comes to us in this delicate transitional period when humanity could, it is sensed, move on to a much more spiritual and happier world?

Music, infinitely more than entertainment, is a powerful weapon for neutralizing negativity in human hearts and creating happiness and harmony.

Bertrand Canac

Dhrupad music lover

Transcendental Meditation teacher

Researcher in Vedic sciences